A few years ago, Peter was working on a big presentation. The way he tells it, he spent several late nights tweaking the deck to be beautiful, the storytelling to be compelling, and the takeaways to be clear and inspiring. The afternoon before the presentation, he did a dry run with a few stakeholders, expecting some strong positive advice on work he was proud of, only to discover that he’d misunderstood the key goal of the presentation.

We’ve probably all been there, knowing we should get early feedback on our work but, deep-down, wanting to wait until everything’s polished and we feel proud of the product.

Why Getting Early Feedback Is So Hard

When it comes to sharing our work, waiting longer just makes intuitive sense. After all, the more complete the work is:

- The more likely reviewers will understand and appreciate it

- The less explaining we’ll have to do

- The more confident we’ll be that it represents our best thinking

- The better we’ll look

This makes perfect sense because competence is a core human motivation factor. We want to be seen as thorough and good at our jobs, and sharing something that is clearly not done requires a level of vulnerability that’s sometimes hard to muster.

On top of that, giving good feedback is a skill that’s in short supply. Especially when the work isn’t fully developed, reviewers might have a hard time providing helpful comments. Most reviewers lean towards one end of a feedback spectrum:

- At one end, reviewers “tell it like it is,” assuming their opinion is the truth. You may appreciate their directness, but you often leave wondering if they value anything that you did.

- On the other end, reviewers limit their comments to positive encouragement and compliments, holding back useful criticism out of fear of damaging the relationship.

(Don’t get us started on the terrible advice to use the “feedback sandwich,” which research shows can lead to worse outcomes than no feedback at all.)

Our Search for a Better Way

So, at Humanizing Work, we dug into the research on feedback, and we started experimenting. The result is a structured approach to asking for and receiving feedback on early drafts of just about anything.

Getting early feedback on an idea used to make me feel uncomfortably vulnerable, so I’d avoid doing it. But using this feedback approach has almost completely erased that concern for me. We’ve seen the same on our team and with our clients. It’s been a huge breakthrough.

A Structured Approach to Early Feedback

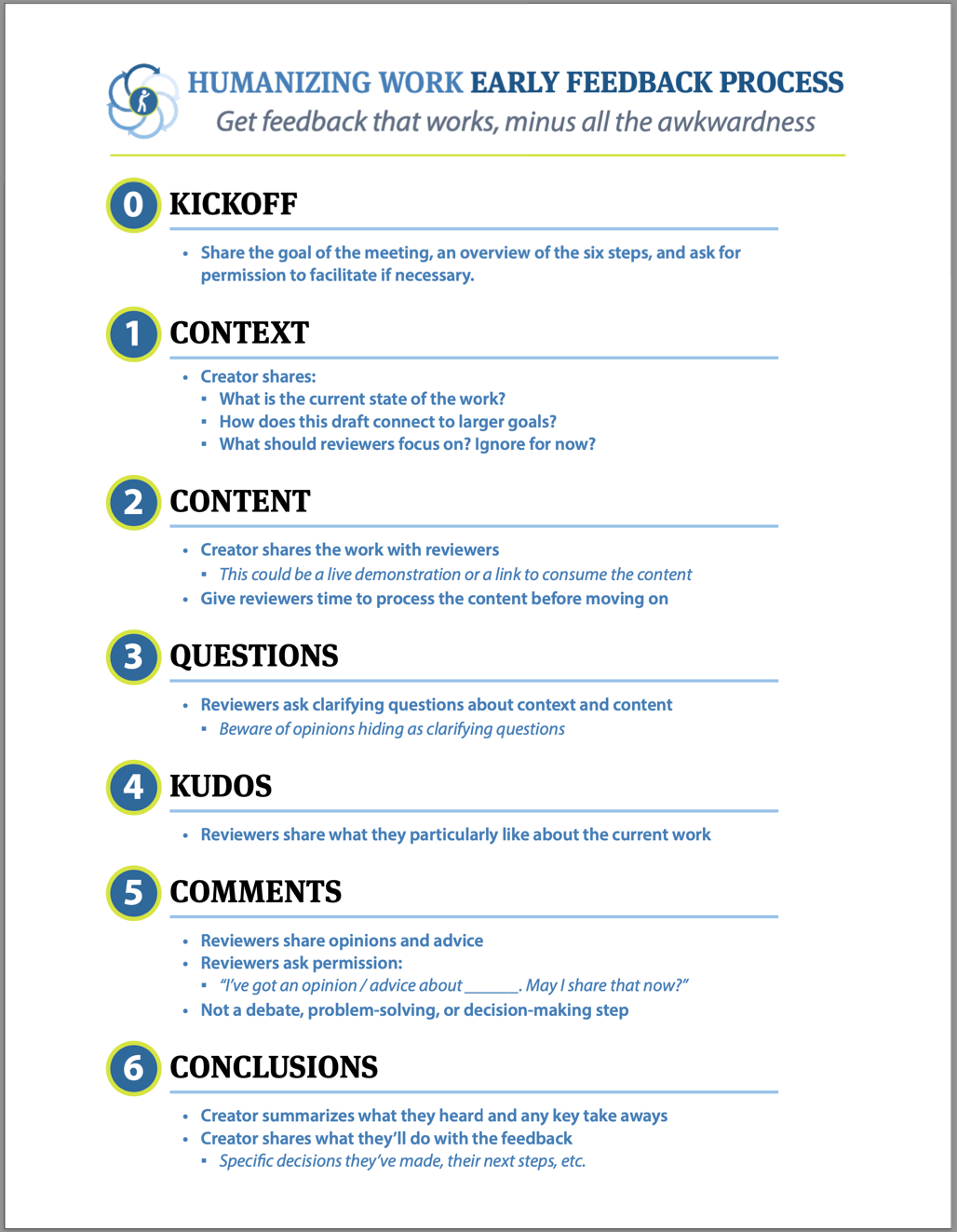

Here’s our six-step process for getting great feedback on a work-in-progress:

1. Context

The creator provides context about what the reviewers are about to see, such as:

The creator provides context about what the reviewers are about to see, such as:

- Where they are in the process

- Decisions they’ve already made

- Areas they’d like reviewers to focus on

- Areas they can ignore for now

- Any placeholders or incomplete sections

This context-setting helps reviewers know where to focus and how this draft fits into the bigger picture.

2. Content

The creator shares the content so reviewers can read through it. Give reviewers enough time to digest the material without interruptions.

3. Questions

The creator asks, “What was unclear to you?” or “What could I clarify?”

This step is about making sure everyone has a basic understanding of the context and content before moving on. Good clarifying questions often sound like “When you used this term, it was unfamiliar to me. What did you mean by that?” or “What other structures did you consider before picking this one?”

Be careful not to ask opinion-disguised-as-questions here, like “Did you consider taking a narrative approach vs. bullet points?” Those belong in step 5.

4. Kudos

The creator asks, “What did you particularly like about this draft? What stood out to you?”

We do this *before* asking for advice or other feedback because it meets the need for a sense of competency before hearing ways the content could be improved. It’s not just “softening the blow.” These should be honest reflections of what reviewers appreciated about the work.

The discipline of looking for what’s good helps highlight things reviewers genuinely like but might not have mentioned because they assumed the creator already knew it was good.

5. Comments

Now, we move to the feedback about what could be different. The creator asks, “What opinions or advice do you have about this?”

Reviewers frame their feedback in a very specific way:

- First, they identify whether it’s an opinion (what they thought about the work) or advice (what they think the creator should do next)

- Then, they use this sentence structure: “I have an [opinion/advice] about [specific aspect]. May I share that now?”

For example: “I have an opinion about the way you’ve described the target customer’s pain in this section. May I share that now?” or “I have some advice about how to tighten up that third paragraph. Is it ok to share that with you?”

Asking permission feels awkward at first, but it does something magical. It shifts the power in the room. The creator gets to decide to receive the feedback and knows what it’s about so they can mentally prepare.

Framing it as an opinion or advice means it’s not an invitation to debate—it’s just information the creator can choose to act on, or not.

During this step, avoid argument or debate about the merits of the opinion or advice. The creator should make sure they understand the feedback by asking clarifying questions, but they don’t need to explain why they agree or disagree.

We’ve found in a group setting it usually works best for someone to give one piece of option or advice and then let someone else give one instead of each person batching up their feedback. It feels more energetic and collaborative and less heavy.

6. Conclusions

Finally, the creator summarizes their conclusions based on the feedback. This could be:

- Major themes they want to mirror back to reviewers

- Specific actions they plan to take

- An expression of appreciation for the reviewers’ time and insights

The creator doesn’t need to commit to specific actions on all feedback. They might simply say they’ll consider certain suggestions or note themes they heard.

Where to Use This Process

This feedback approach can supercharge many different types of work:

- Design projects: Get early feedback on initial concepts or prototypes

- Research: Get feedback on questions, methodology, or thesis statements

- Marketing campaigns: Get input on initial concepts, target audience, key messages, or creative assets

- Organizational change: Get early feedback from employees and stakeholders on where resistance might lie

- Presentations: Get early feedback on key focus, storytelling, visuals, and structure

- Product development: Get feedback on incremental development, such as in a Scrum Sprint Review

You can use this process in person or via video call, one-on-one or with a team.

For asynchronous feedback, organize the feedback around each of the three main response categories (Questions, Kudos, and Comments). On our team, we do this in Slack. Richard might share a draft of a newsletter (like this one) in our #needsreview channel. Then, Peter and Angie will chime in on the thread with feedback prefaced with Q, K, O, or A (we distinguish opinions and advice with this shorthand). Async feedback works well for lower-stakes, routine reviews. Live feedback is better for more significant or non-standard pieces of work.

Try It Yourself

Getting early feedback used to be awkward and rarely useful. But with this structured approach, it becomes easy and generates great results.

If you’ve been holding off on sharing an early draft of something, try this out and see how different it feels. Even slightly clumsy first attempts to use it have yielded much better feedback with our clients!

If you try it, we’d love to hear how it goes — reply and let us know.

Want a handy reference guide for this process? Download our Early Feedback Process guide.

Last updated