The single biggest mistake that teams make with their backlogs and individuals make with their todo lists happens to be the most natural thing to do in any work management tool, from Jira to Apple Reminders.

When you think of something that needs to be done (or that could be done), it makes sense to want to capture it, to get it out of your head. And so, the creators of work management tools oh so helpfully make it easy to add new items.

If you’ve ever been on a Scrum team, you’ve experienced something like this: You finish a sprint with, say, 10 backlog items done. Meanwhile, over that same sprint, your backlog got 20 items longer.

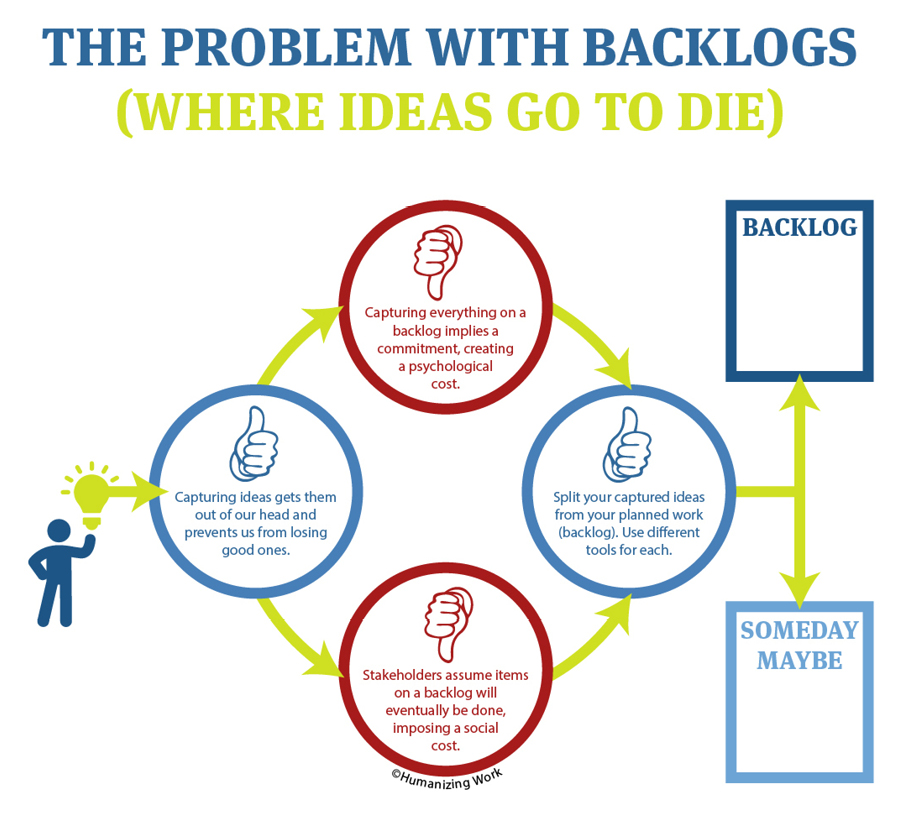

In practice, backlogs are typically the place where everything you might do ends up. Same with most people’s personal todo lists. This is good for not losing track of that occasional great idea. But it comes with some high psychological and social costs.

Here’s the problem and what to do instead.

In his classic book on personal productivity, Getting Things Done, David Allen writes,

A basic truism I have discovered over decades of coaching and training thousands of people is that most stress they experience comes from inappropriately managed commitments they make or accept. Even those who are not consciously “stressed out” will invariably experience greater relaxation, better focus, and increased productive energy when they learn more effectively to control the “open loops” of their lives. You’ve probably made many more agreements with yourself than you realize, and every single one of them—big or little—is being tracked by a less-than-conscious part of you. (pp. 13-14)

Backlog items are, in Allen’s terms, open loops. They’re implicit commitments to do some work at some point in the future.

And if you’re on a “finish 10, add 20” trajectory with your backlog, your brain knows those commitments are never going to be kept. That’s a chronic source of stress.

We occasionally survey product owners about this. Unless they’ve deliberately done something specific to avoid the endless backlog, a typical PO manages a backlog 1-4 years long, 50-75% of which will never make it to the top and get built. No wonder they’re stressed!

The cost isn’t just psychological, though. It’s also social.

Your brain knows a backlog item is an implicit commitment to future work. Your stakeholders’ brains know it, too. Consider how the conversation changes. Before something goes on the backlog, the question sounds like, “Is this something your team could build?” Once it ends up on the backlog—even if it’s at the bottom and no explicit delivery commitment has been made—the question changes to, “When is the team going to build such-and-such?”

(The honest answer? “Probably never.” But it’s rarely politically wise to say so. And thus, the implicit commitments pile up.)

Those long backlogs become the place where stakeholder dreams go to die. The social cost here is relational friction, disappointment, undermined trust, and collective stress.

Given these forces:

- Capturing ideas keeps us from losing the good ones

- But capturing everything on a backlog imposes psychological costs

- And capturing everything on a backlog imposes social costs

What should we do?

Separate the two jobs we often ask backlogs to do. Capturing ideas and planning work are different jobs. Use different tools.

Capture everything you might do somewhere. Keep it as high-level as you can. Or, at the very least, provide a high-level view along with the ability to dig into details as needed. It’s hard to manage a list of 200 tiny ideas. This is *not* your backlog. It’s a different thing. It might even be more than one thing. If your team does work from multiple demand sources, each one might choose to manage their own list of ideas. Our clients have had good results with that shift.

Then, make your backlog represent work you actually intend to do. Putting an item on the backlog should be an 80% or better confidence commitment to actually getting it done. And refining items on your backlog should feel like progressive discovery and elaboration, not churn. See our PO Board episode of the Humanizing Work Show for a way to model a backlog as a Kanban system so its easier to have just enough detail, just in time.

If you have one of those 2-year-long backlogs full of work that’ll never get done, you might have to declare “backlog bankruptcy.” Move the current backlog to another list, “Things we knew about as of June 2024,” and then build a realistic backlog from the top down.

You can do the same thing with your personal work. Get everything out of your head, but not right into your todo list. Capture it somewhere, and then decide what you actually want to commit to. (Getting Things Done is an elegant system for this, by the way.)

Want help building your system for capturing ideas and making sustainable commitments? Visit the contact page at humanizingwork.com and schedule a free discovery call to see if there’s a good fit.

Last updated