Consensus cultures offer two significant advantages over highly directive ones. First, considering multiple perspectives often leads to better decision outcomes. Second, when people are invited to provide input on a decision—especially when they feel their input was genuinely considered—they are more committed to the decision, even if the final outcome isn’t what they initially hoped for.

However, there’s a major downside to consensus-driven decision-making: speed. When every decision requires discussion and agreement from everyone, the process can become unnecessarily slow.

So, how can we capture the benefits of diverse perspectives and high commitment while avoiding the pitfalls of a slow decision-making process?

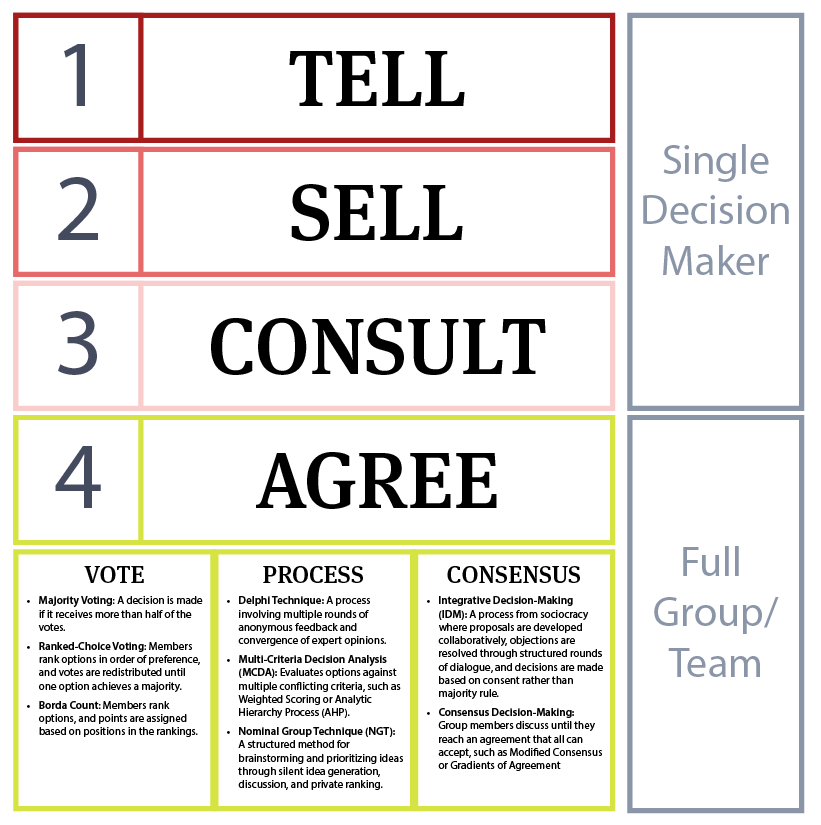

First, not every decision needs input from everyone. To clarify who will make a decision and how they’ll involve others, we’ve adapted Jurgen Appelo’s Seven Levels of Delegation model, as illustrated below.

Many decisions can be made by a single individual with expertise in the relevant area. Using the decision levels from the illustration, start by choosing how the decision-maker will involve others at levels 1, 2, or 3.

At level 1, the decision-maker simply makes the decision and informs others. This approach is often appropriate during a crisis, when the stakes are low, outcomes are predictable, or when a single person has significantly more expertise and authority in the area than others.

At level 2, the decision-maker makes the decision and then “sells” it to stakeholders, who can ask for clarification, justification, and implementation details. Knowing they’ll need to answer questions helps the decision-maker anticipate potential objections or concerns, typically improving the decision outcome.

At level 3, input from others is considered before making the decision. The decision-maker creates a draft proposal and seeks feedback using something like the Humanizing Work Feedback Process before finalizing the decision.

In levels 1-3, a single decision-maker is empowered to make the decision and is accountable for the results. At levels 1 and 2, the decision is communicated after it’s made, while at level 3, input is gathered beforehand.

We strongly recommend shifting most decisions that would otherwise require consensus to Level 3. This approach captures the benefits of input while minimizing the downsides of a slow process.

Some decisions, however, truly benefit from consensus—like adopting a team working agreement, making a shared commitment to a scope of work, or aligning on a standard or process with major implications.

For these cases, there is a spectrum of processes to reach a decision. This can range from a simple vote, which can sometimes be a fast route to a group decision, to one of several facilitated structures appropriate for different contexts, and finally, true consensus-based decision-making.

This approach to decision-making is role-independent, so it can be combined with role-based models like RAPID, DACI, or RACI to provide additional clarity on how people with different roles will participate in the decision-making process.

So, the next time you need to make a decision, start by deciding how you’ll decide—favoring the empowerment of a single decision-maker and defining what role others should play in influencing that decision.

Last updated